These pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. showcase his life, legacy and impact as a civil rights leader

25 Pictures of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Legacy

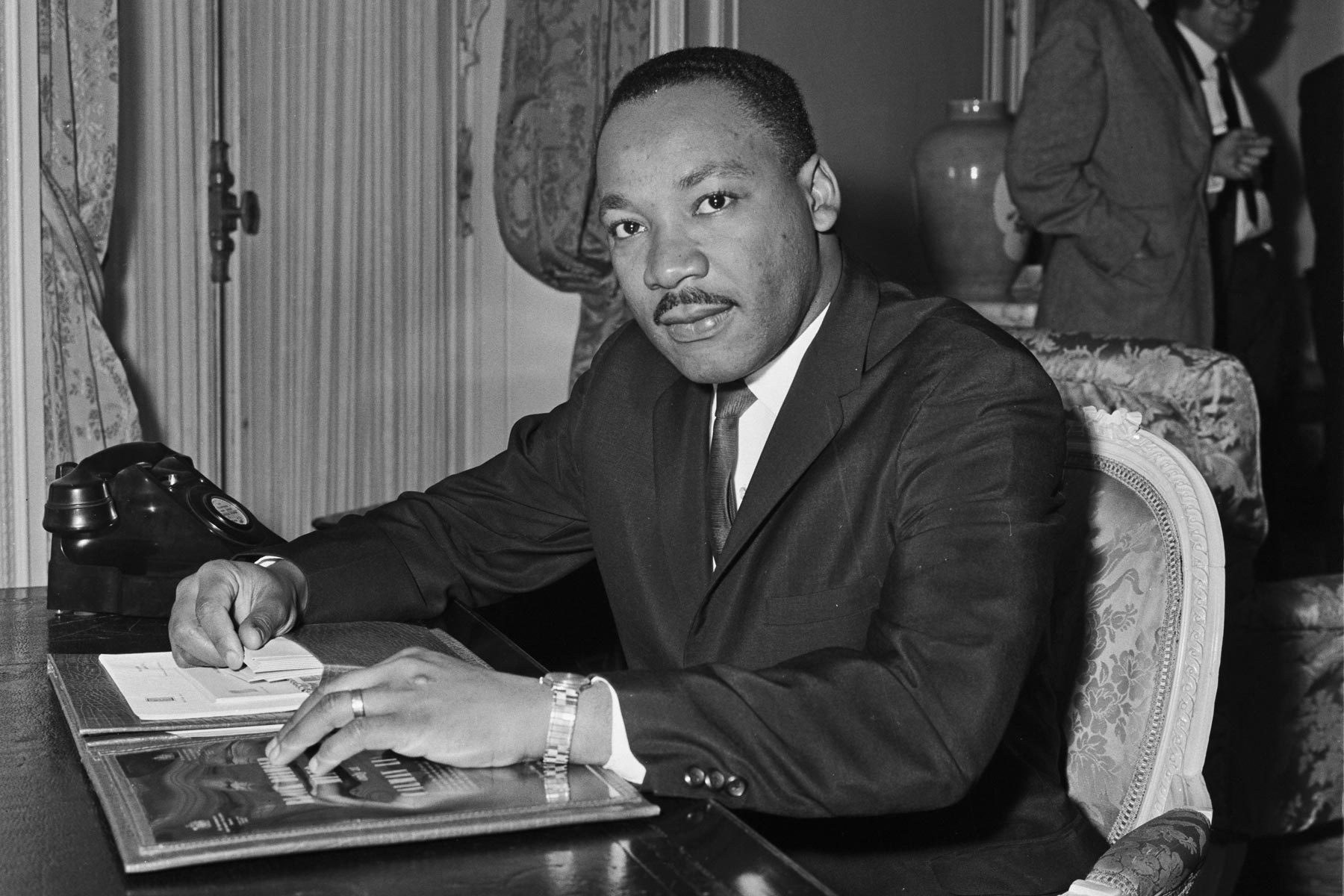

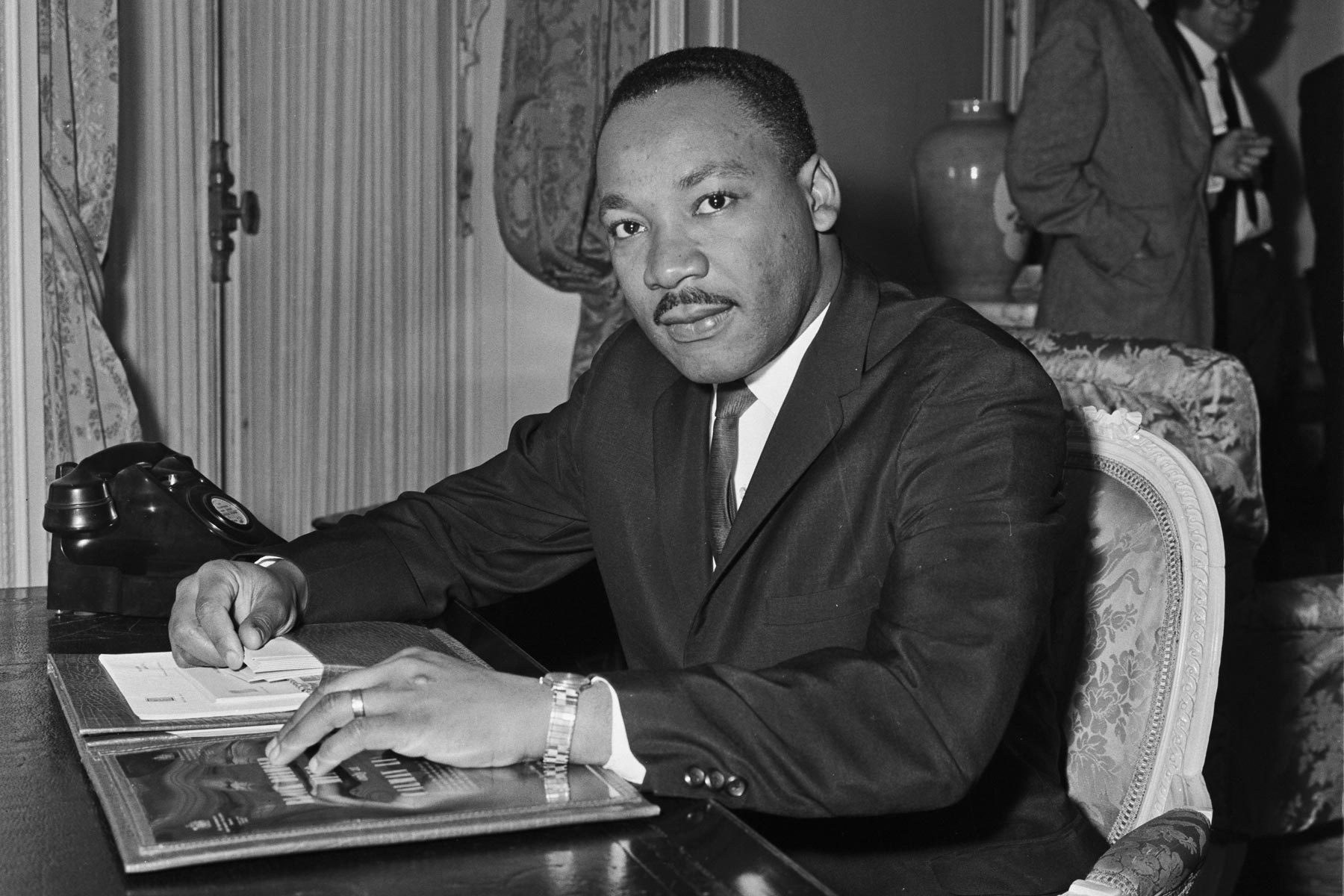

The reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Here’s one of the pictures of Martin Luther King where we see him as a younger adult. King was an associate pastor at his father’s church in Atlanta, where he eventually became the reverend. He gave credit to his father, Martin Luther King Sr., for inspiring him to join the ministry, saying, “He set forth a noble example that I didn’t [mind] following.” In this MLK picture, he is shown speaking with parishioners in Montgomery, Alabama, after delivering a sermon on May 13, 1956.

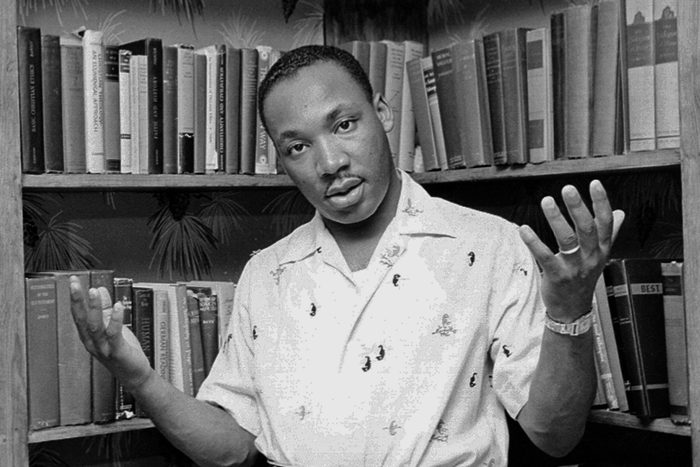

King and his Bible

Here, King is at home, in front of his library. One book he couldn’t live without? His Bible, which reportedly traveled with him wherever he went. Another fun Martin Luther King Jr. fact? When President Obama was sworn in at his January 2013 inauguration, he rested his hand on King’s Bible.

Daddy dearest

When he wasn’t freedom-fighting across America, MLK was a doting father of four. In this picture of Martin Luther King Jr., he’s shown spending quality time with his daughter Yolanda and wife Coretta, at the couple’s family home in Montgomery, Alabama, in May 1956.

A plan for change

Before the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, intended to protest segregation on public transportation, King held a meeting on Jan. 27, 1956, to plan the boycott’s strategy with his advisors and organizers. Rosa Parks, also known as “the mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” sits in the front row.

Under arrest

During the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott, King and several other local civil rights leaders who helped organize the protest were arrested. King spent months in jail during the boycott, which lasted nearly a year, until the Supreme Court ruled that segregation on buses is unconstitutional.

Mug shot

In this picture of King, he sits for his mug shot after being booked in the Montgomery jail as a result of leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott—a life-changing moment in American history. Today, after nearly seven decades, Alabama officials say they are considering wiping the records clean for Rosa Parks and King for their noble acts.

His home bombed, King urges nonviolence

During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a white supremacist terrorist planted a bomb on the patio of King’s home that was strong enough to blow out the house’s windows. The family was home at the time, and although they were shaken up by the blast, they were not harmed. Here, King addresses a crowd from his front porch after the bombing, urging them not to resort to violence and to remain calm as they peacefully resist segregation.

King meeting Vice President Richard Nixon

King had a complicated relationship with Richard Nixon, according to Stanford University’s King Institute. Initially, King was unimpressed with Nixon’s interest in—and commitment to—civil rights matters, but he later warmed to Nixon after two meetings in 1957, one of which is pictured here. His feelings changed again when Nixon failed to come to his defense after King was arrested for his participation in a sit-in in Atlanta in 1960.

Hospitalized after surviving an assault in 1958

King was in critical condition at New York’s Harlem Hospital following an attack at a book signing in which a mentally ill woman stabbed him with a steel letter opener. King bore no ill will toward his attacker and addressed the attack in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech on April 3, 1968, which he gave the day before he was assassinated.

A pilgrimage to India in 1959

King, who was sometimes referred to as “America’s Gandhi,” described Mahatma Gandhi as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change,” according to Stanford University. To the group of reporters gathered at the airport, King, pictured here with his entourage, said, “To other countries, I may go as a tourist, but to India, I come as a pilgrim.”

Going international

King deplaned in London to appear on the BBC show Face to Face in October 1961. During the interview, he talked about his early days and some of the most defining moments of the Civil Rights Movement as he saw it, and confessed that he experienced times of “fear and loneliness.”

Released from jail … again

Reporters swarmed King after he was released from jail in Albany, Georgia, in 1962, following his arrest for leading anti-racism protestors without a permit. A judge ordered King and a fellow activist to pay a $178 fine or serve 45 days in jail. King chose the sentence.

“We chose to serve our time because we feel so deeply about the plight of more than 700 others who have yet to be tried,” King said. “We have experienced the racist tactics of attempting to bankrupt the movement in the South through excessive bail and extended court fights. The time has now come when we must practice civil disobedience in a true sense or delay our freedom thrust for long years.”

Two days into the sentence, at the time of this picture of Martin Luther King, authorities informed King that an unidentified man had paid his bail, ensuring his early release.

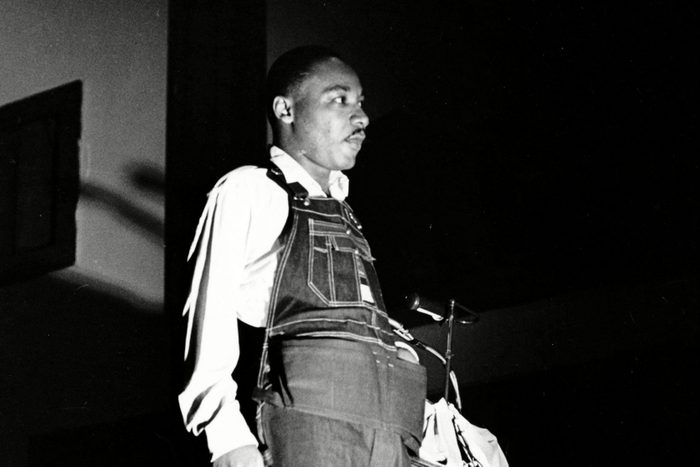

The overalls movement

In April 1963, King helped lead an anti-segregation protest in Birmingham, Alabama—a nonviolent one, of course, and it included church kneel-ins as well as regular sit-ins and a march on the county building to register Black voters. He’s pictured here on April 6, asking supporters to join him in wearing overalls until Easter as part of the protest. The denim work clothes were once considered sharecropper wear; King wore the overalls to symbolize how little progress had been made since Reconstruction. On April 12, King was arrested and kept in solitary confinement; his jailers refused his request to speak with his wife—she had just delivered their fourth child—until President Kennedy intervened.

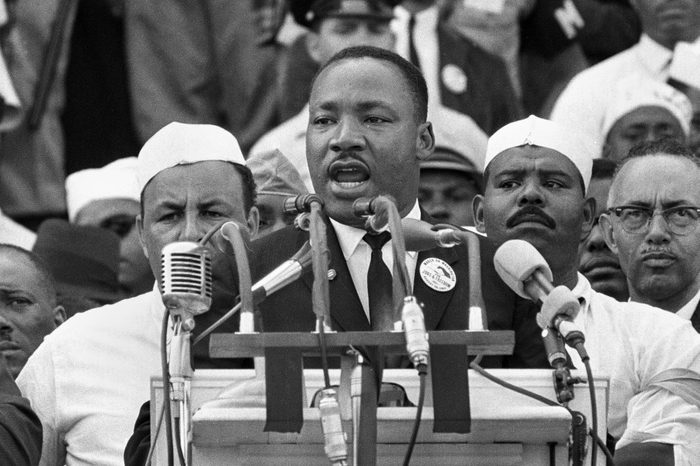

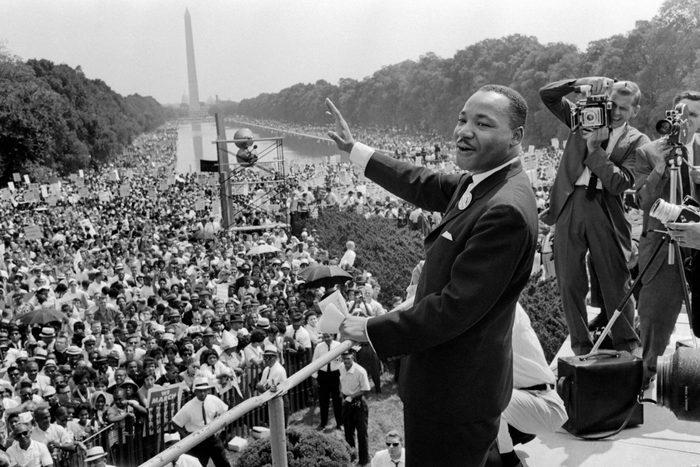

“I have a dream …”

We can’t share MLK pictures without commemorating King’s iconic speech. On Aug. 28, 1963, during the March on Washington in front of the Lincoln Memorial, King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which contained many powerful quotes about the fight against racism. He urged America to “make real the promises of democracy” and called the day “the greatest demonstration of freedom in the history of the United States.” In one of the most historic pictures of Martin Luther King Jr., he’s shown giving that speech before thousands of civil rights supporters.

At the White House

After he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, King and the organizers of the March on Washington met with President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House. The organizers had originally wanted to meet the morning of the march, but the president demurred. According to presidential speechwriter Ted Sorensen, “He felt that if they should present him with a list of demands he could not meet, the march would then turn into an anti-Kennedy protest.”

King with Malcolm X

While King protested segregation through nonviolent means, another civil rights leader, Malcolm X (formerly, Malcolm Little), advocated for racial separatism through any means necessary. The two met only once—in Washington, D.C., at a press conference on March 26, 1964, pictured here. At the end of the conference, King shook Malcolm X’s hand in an offer of “kindness and reconciliation.”

A meeting for peace

In July 1964, after an off-duty White police officer shot and killed a young Black man in New York City, a six-day race riot erupted, prompting King to fly to New York City, where he met with leaders at the NAACP’s headquarters. In a signed letter, most of the group called for peace and “a broad curtailment, if not total moratorium,” on mass demonstrations until after the November presidential election between incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson and his Republican challenger, Barry Goldwater.

Why? They wanted to focus the public’s attention on voter registration, specifically Black voters’ registration. You may recognize that seated alongside King was fellow activist and future congressman John Lewis, who disagreed with King, saying, “Demonstrations must continue. The pressure must be kept on.”

The Civil Rights Act

In one of the most noteworthy pictures of Martin Luther King Jr., King shakes hands with President Lyndon Johnson after he signs the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964. It was a historic moment, with the act ending segregation in public schools and deeming discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, religion or national origin unconstitutional.

A visit to the World’s Fair

Later that summer, MLK treated his daughter Yolanda and son Martin Luther King III to a visit to the World’s Fair in New York City. Although his son Martin was only 10 years old when MLK was assassinated, he says he has countless fond memories of his father. “Yet a half-century later, the most powerful feeling I still have is gratitude, not only for the wonderful times I shared with my father but also for having a strong mother, who inspired me with the way she raised us, kept her promise to make sure our father would be remembered and continued to serve humanity until her death in 2006.”

A march for voting rights

King led a five-day, 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest Bloody Sunday (March 7, 1965), an earlier march during which nonviolent supporters of voting rights reform were beaten and otherwise assaulted by law enforcement. The march helped prompt Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which gave Black people better access to the polls—at the time of the march, only 2% of the Black population in Selma were registered voters.

When push comes to shove

In this picture, a policeman forcefully shoves King during the 220-mile March Against Fear in Mississippi, on June 8, 1966. Martin Luther King Jr. always centered his movement on peaceful protest. “Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon,” King said, “which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it. It is a sword that heals.”

Follow the leader

In June 1966, King led Mississippi freedom marchers into Yalobusha County, Mississippi. The marchers went on to hold a voter registration drive aimed at increasing the Black vote amid rampant voter intimidation and suppression tactics.

The mouth that roared

King turned up the volume for an estimated 30,000 supporters at a Chicago Freedom Movement rally in Soldier Field on July 10, 1966. The day would later be dubbed “Freedom Sunday,” an ode to the Chicago Freedom Movement, which focused on the unfair housing practices experienced by Black communities in the city. “This day we must declare our own Emancipation Proclamation,” said an impassioned King. “This day we must commit ourselves to make any sacrifice necessary to change Chicago. This day we must decide to fill up the jails of Chicago, if necessary, in order to end slums.”

The great orator wasn’t always so confident with public speaking. Historians note that while King attended a seminary, he received a C for public speaking.

Anti-warmonger

King delivered a speech on the Vietnam War and his anti-war beliefs to a crowd of 7,000 people in May 1967 at the University of California’s Berkeley Sproul Plaza.

King’s last appearance

There are many pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. that we don’t want to forget—and one of those is his last appearance. On April 4, 1968, King was killed by a single rifle shot as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. He’s pictured here on April 3 on that very balcony, preparing for the next day’s speech with three other civil rights leaders—Hosea Williams, Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy.

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Stanford University: “The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute”

- John F. Kennedy Library and Museum: “Theodore C. Sorensen Oral History Interview – JFK #5, 5/3/1964”

- National Constitution Center: “Five interesting facts on the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr.”